The key to living a full life is love, and without love for their work, many Canarians would have given up their profession a long time ago. The cochineal collector, the gofio miller, the luchador, the guarapero or the guachinchero are all professions that carry immense pride in their work. These traditions continue to this day, defining the Canarian character, rooted in the culture and character of its people.

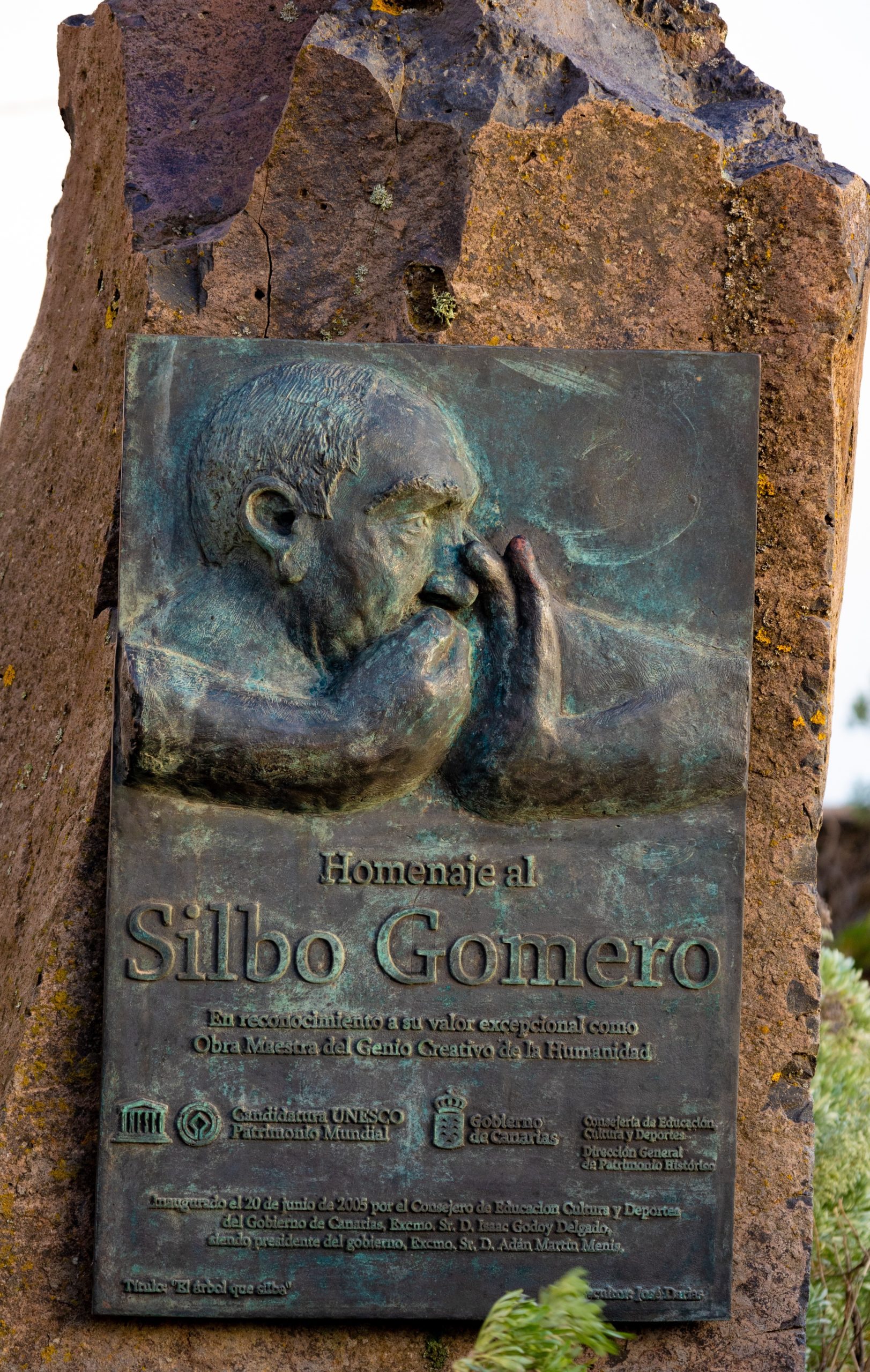

Whistler

The Silbo Gomero is a whistled language originated by the aborigines of this island of high mountains and vibrant valleys. For centuries, its inhabitants have been whistling to each other from one place to another, oftentimes many kilometers away. The echo and active listening do the rest. Master whistler Diego Arteaga learned to whistle from his grandfather. Whistles between family members to call for lunch, to let people know they’ve left school or because someone is sick can be heard throughout the countryside. Today it is taught in the island’s schools through the Silbo Gomero Cultural Association. It is recognized as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. More than 4,000 concepts can be expressed with whistles, distinguished by their tone and their interruption or continuity.

Guarapero

When walking along the roads and paths of La Gomera, it is not uncommon to see buckets hanging from threads on the Canary Island palm trees that line most of the landscapes near the coast. With those buckets the guarapero collects the guarapo, or sap. It is a tradition with more than 500 years of history that is a heritage asset of the island. This guarapo is used in the Canary gastronomy to add sweet flavour, to coat food, to make desserts or to mix it with different drinks and juices. Josué Caimán, guarapero, explains that the “curing of the palm tree is done when the evening falls, with the coolness of the night, and it is then harvested in the morning. It is harvested in the morning when the sun is not beating down hard,” he stresses, “because the guarapo cannot receive heat, as it ferments”. Curiously, the rain-fed palms produce a sweeter guarapo and those closer to the water produce the guarapo with less sweetness and more liquid.

The guarapo is extracted after making a cut in the upper tissues of the palm tree, after removing the young leaves. The buckets used has capacities of 20 liters and in one night can be filled “up to half or up to 70% of the bucket, since the bees and bumblebees also drink it,” Caimán points out.

Canarian wrestler

Vicente Cáceres Suárez, known in the wrestling arena as Tito Cáceres, is a wrestler, trainer and coach proudly in a profession that dates back to the times of the aboriginal Canary Islanders, the inhabitants of the archipelago before the Castilian conquest.

Canarian wrestling is a sport that can be practiced at any age, from childhood to adulthood. “There are people who have a lot of talent and a lot of ability, but you have to work at it.” He also stresses, “it is an integrative sport, that does not distinguish between girls and boys or children with disabilities. Anyone can practice it, depending on their level, of course,” he assures.

Tito Cáceres feels the commitment to “continue working on a legacy left by our ancestors with this noble sport”. Canarian wrestling is an expression of the values of the inhabitants of the islands: “From the start,” he explains, “we teach them that they must have a lot of respect and honesty. We also teach them companionship, commitment to discipline and work for themselves and others, because without a partner there is no evolution.”

Guachinchera

With wines from their own vineyards and food with a taste of home, guachinches are native to Tenerife (seasonal establishments created by winemakers to sell their wine, accompanied by something to eat) but they can be found all over the Canary Islands. Eva Diaz Perez was a nurse by profession but jumped at the chance to take over a guachinche in Icod de los vinos 11 years ago. Now customers from all over the world, some as far away as Australia, come to to sit at her tables. “I consider myself very lucky to work in a guachinche, it is very comforting,” she assures while laughing when asked the secret of her success: “I would say treat others as you would like to be treated and smile, always smile, even if you have a bad day,” she stresses.

The name “guachinche” comes from the English expression “I’m watching you!”, which English shoppers used when they wanted to try the products of the land before purchasing.

Miller

The Molino de Gofio La Máquina, in La Orotava, is 100 years old and the gofio is still made in the same way as it was then. Its owner and miller, Alexis García Ramos, explains that “we select the corn, toast it, let it cool and then grind it. In Canary Island households,” he says, “people still eat a lot of gofio, especially millet (corn), and since it is also a superfood, hikers and many visitors buy it for excursions.

The artisan gofio, in bags and before in sacks, is made in stone mills, without additives, from roasted corn, wheat and barley (mainly), which results in a product that is similar to flour in texture. Gofio has been used to feed Canary Islanders in times of scarcity as well as in times of prosperity.

Cochineal harvester

The extraction of the cochineal put the Canary Islands in the center of the Chinese Silk Road thanks to the fact that, once collected from the cochineal, a valuable red dye for fabrics is extracted from it. Carmen Díaz, a spinner at the Silk Museum in El Paso, on the island of La Palma, began learning this trade as a child while tending silkworms and spinning her first cloths on the looms. “You have to take a container and, with a spoon, scrape the little white balls that form on its surface. This is then converted by a natural process into ink in shades of pink, red and mauve. Today, the fabrics of the Museo de la Seda de La Palma are still dyed with cochineal,” Díaz points out.

Its period of greatest commercial splendor was in the 19th century but has been collected in the same way on the islands since the 15th century. It is an insect with great economic importance from which the natural coloring is extracted, composed of two famous substances, carmine and carminic acid. The cochineal, as it is known in the Canary Islands, is a parasite of plants such as the prickly pear cactus and comes from America.